Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau is the largest (~1,500 × 3,500 km), high-elevation (mean of ~5,000 m) topographic

feature on Earth and hosts the thickest crust of any modern orogen, with estimates in southern Tibet of

~70 km (Owens and Zandt, 1997; Nábělek et al., 2009), and up to ~85 km (Wittlinger et al., 2004; Xu et

al., 2015). The Tibetan Plateau formed from the sequential accretion of continental fragments and island

arc terranes beginning during the Paleozoic and culminated with the Cenozoic collision between India and

Asia (Argand, 1922; Yin and Harrison, 2000; Kapp and DeCelles, 2019). The India-Asia collision is

largely thought to have commenced between 60 and 50 Ma (e.g., Rowley, 1996; Hu et al., 2016); however,

some raise the possibility for later collisional onset (e.g., Aitchison et al., 2007; van Hinsbergen et

al., 2012). Despite ongoing ~north-south convergence, the northern Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau interior

are undergoing east-west extension, expressed as an array of approximately north-trending rifts that

extend from the axis of the high Himalayas to the Bangong Suture Zone (Molnar and Tapponnier, 1978;

Taylor and Yin, 2009) (Fig. 1).

Figure

1

Figure

1

Digital elevation model of southern Tibet with major tectonic features. Active structures from

HimaTibetMap (Styron et al., 2010). The basemap is from MapBox Terrain Hillshade. Lake

locations are

from Yan et al. (2019). Data points include only the filtered data (supplemental material [see text

footnote 1]). HW—hanging wall.

The Mesozoic tectonic evolution of the southern Asian margin placed critical initial conditions for the

Cenozoic evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. However, much of the Mesozoic geologic history remains poorly

understood, in part due to structural, magmatic, and erosional modification during the Cenozoic. There

is disagreement even on first-order aspects of the Mesozoic geology in the region. For example, temporal

changes in Mesozoic crustal thickness are largely unknown, and the paleoelevation of the region is

debated. Most tectonic models invoke major shortening and crustal thickening due to shallow subduction

during the Late Cretaceous (e.g., Wen et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2013), possibly pre-conditioning the

southern Asian margin as an Andean-style proto-plateau (Kapp et al., 2007; Lai et al., 2019).

Alternatively, Late Cretaceous to Paleogene shortening may have been punctuated by a 90–70 Ma phase of

extension that led to the rifting of a southern portion of the Gangdese arc and opening of a backarc

ocean basin (Kapp and DeCelles, 2019). These represent two competing end-member hypotheses for the

Mesozoic tectonic evolution of southern Tibet that are testable by answering the question: Was the crust

in southern Tibet thickening or thinning between 90 and 70 Ma?

Contrasting hypotheses about the Cenozoic tectonic evolution of southern Tibet are testable by

quantifying changes in crustal thickness through time. In particular, the Paleocene tectonic evolution

before, during, and after the collision between India and Asia was dependent on initial crustal

thickness, and in part controlled the development of the modern Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau. Building on

the hypothesis tests for the Late Cretaceous, if the crust of the southern Asian margin was thickened

before or during the Paleocene, then this explains why the southern Lhasa Terrane was able to attain

high elevations only a few million years after the onset of continental collisional orogenesis (Ding et

al., 2014; Ingalls et al., 2018). However, if the Paleocene crust was thin, then we can ask the

question: When did the crust attain modern or near modern thickness? Answering this question is a

critical test of alternative tectonic models that suggest rapid surface uplift from relatively low

elevation (and presumably thin crust) during the Miocene (e.g., Harrison et al., 1992; Molnar et al.,

1993) or Pliocene (Dewey et al., 1988) as the product of mantle lithosphere removal (England and

Houseman, 1988). Finally, what happened after the crust was thickened to extreme levels, as we have in

the modern? Did the plateau begin to undergo orogenic collapse (Dewey, 1988) resulting in a net

reduction in crustal thickness and surface elevation that continues to present day (e.g., Ge et al.,

2015), as evidenced by the Miocene onset of east-west extension (e.g., Harrison et al., 1995; Kapp et

al., 2005; Sanchez et al., 2013; Styron et al., 2013, 2015; Sundell et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2019)?

Or did Tibet remain at steady-state elevation during Miocene-to-modern extension (Currie et al., 2005)

with upper crustal thinning and ductile lower crustal flow (e.g., Royden et al., 1997) working to

balance continued crustal thickening at depth driven by the northward underthrusting of India (DeCelles

et al., 2002; Kapp and Guynn, 2004; Styron et al., 2015)?

Igneous rock geochemistry has long been used to estimate qualitative changes in past crustal (e.g.,

Heaman et al., 1990) and lithospheric (e.g., Ellam, 1992) thickness. Trace-element abundances of igneous

rocks have proven particularly useful for tracking changes in crustal thickness (Kay and Mpodozis, 2002;

Paterson and Ducea, 2015). Trace-element ratios provide information on the presence or absence of

minerals such as garnet, plagioclase, and amphibole because their formation is pressure dependent, and

each has an affinity for specific trace elements (e.g., Hildreth and Moorbath, 1988). For example, Y and

Yb are preferentially incorporated into amphibole and garnet in magmatic melt residues, whereas Sr and

La have a higher affinity for plagioclase (Fig. 2A). Thus, high Sr/Y and La/Yb can be used to infer a

higher abundance of garnet and amphibole and a lower abundance of plagioclase, and may be used as a

proxy for assessing the depth of parent melt bodies during crustal differentiation in the lower crust

(Heaman et al., 1990). These ratios have been calibrated to modern crustal thickness and paired with

geochronological data to provide quantitative estimates of crustal thickness and paleoelevation through

time (e.g., Chapman et al., 2015; Profeta et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017, 2020; Farner and Lee, 2017).

Figure

2

Figure

2

(A) Schematic partitioning diagram for Y and Yb into minerals stable at high lithostatic pressures >1

GPa such as garnet and amphibole. (B–D) Empirical calibrations using known crustal thicknesses from data

compiled in Profeta et al. (2015) based on (B) multiple linear regression of ln(Sr/Y) (

x-axis),

ln(La/Yb) (

y-axis), and crustal thickness (

z-axis); (C) simple linear regression of

ln(Sr/Y) and crustal thickness; and (D) simple linear regression of ln(La/Yb) and crustal thickness.

Equations in parts B–D include 95% confidence intervals for each coefficient. Coefficient uncertainties

should not be propagated when applying these equations to calculate crustal thickness; rather, the 2s

(95% confidence interval) residuals (modeled fits subtracted from known crustal thicknesses) are more

representative of the calibration uncertainty.

We build on recent efforts to empirically calibrate trace-element ratios of igneous rocks to crustal

thickness and apply these revised calibrations to the eastern Gangdese mountains in southern Tibet (Fig.

1). This region has been the focus of several studies attempting to reconstruct the crustal thickness

using trace-element proxies (e.g., Zhu et al., 2017) as well as radiogenic isotopic systems such as Nd

and Hf (Zhu et al., 2017; Alexander et al., 2019; DePaolo et al., 2019), and highlight discrepancies in

different geochemical proxies of crustal thickness. As such, we first focus on developing a new approach

to estimate crustal thickness from Sr/Y and La/Yb, both for individual ratios, and in paired Sr/Y–La/Yb

calibration. We then apply these recalibrated proxies to data from the Gangdese mountains to test

hypotheses explaining the Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonic evolution of southern Tibet.

Methods

Sr/Y and La/Yb (the latter normalized to the chondritic reservoir) were empirically calibrated using a

modified approach reported in Profeta et al. (2015). Calibrations are based on simple linear regression

of ln(Sr/Y)–km and ln(La/Yb)–km; and multiple linear regression of ln(Sr/Y)–ln(La/Yb)–km (Figs. 2B–2D).

We also tested simple linear regression of ln(Sr/Y) × ln(La/Yb)–km (see GSA Supplemental

Material1). Regression coefficients and residuals (known minus modeled thickness) are

reported at 95% confidence (±2s).

The revised proxies were applied to geochemical data compiled in the Tibetan Magmatism Database (Chapman

and Kapp, 2017). Geochemical data used here comes from rocks collected in an area between 29 and 31°N

and 89 and 92°E. Data were filtered following methods reported in Profeta et al. (2015) where samples

outside compositions of 55%–68% SiO2, 0%–4% MgO, and 0.05–0.2% Rb/Sr are excluded to avoid

mantle-generated mafic rocks, high-silica felsic rocks, and rocks formed from melting of metasedimentary

rocks. Filtering reduced the number of samples considered from 815 to 190 (supplemental material; see

footnote 1).

We calculated temporal changes in crustal thickness based on multiple linear regression of

ln(Sr/Y)–ln(La/Yb)–km (Fig. 2B). Each estimate of crustal thickness is assigned uncertainty of ±5 m.y.

and ±10 km; the former is set arbitrarily because many samples in the database do not have reported

uncertainty, and the latter is based on residuals calculated during proxy calibration (Fig. 2). Temporal

trends were calculated using two different methods. The first method employs Gaussian kernel regression

(Horová et al., 2012), a non-parametric technique commonly used to find nonlinear trends in noisy

bivariate data; we used a 5 m.y. kernel width, an arbitrary parameter selected based on sensitivity

testing for over- and under-smoothing. The second method involves calculating linear rates between

temporal segments bracketed by clusters of data that show significant changes in crustal thickness:

200–150 Ma, 100–65 Ma, and 65–30 Ma. Trends are reported as the mean ±2s calculated from bootstrap

resampling 190 selections from the data with replacement 10,000 times.

Results

Proxy calibration using simple linear regression of ln(Sr/Y)–km and ln(La/Yb)–km yields

Crustal Thickness = (19.6 ± 4.3) × ln(Sr/Y) + (−24.0 ±

12.3), (1)

and

Crustal Thickness = (17.0 ± 3.7) × ln(La/Yb) + (6.9 ±

5.8), (2)

whereas multiple linear regression of ln(Sr/Y)–ln(La/Yb)–km calibration yields

Crustal Thickness = (−10.6 ± 16.9) + (10.3 ± 9.5) × ln(Sr/Y) + (8.8 ± 8.2) × ln(La/Yb). (3)

Crustal thickness corresponds to the depth of the Moho in km, and coefficients are ±2s (Figs. 2B–2D and

supplemental material [see footnote 1]). Although we report uncertainties for the individual

coefficients, propagating these uncertainties results in wildly variable (and often unrealistic) crustal

thickness estimates, largely due to the highly variable slope. Hence, we ascribe uncertainties based on

the 2s range of residuals (Figs. 2B–2D). Residuals are ~11 km based on simple linear regression of

Sr/Y–km and La/Yb–km, and ~8 km based on multiple linear regression of Sr/Y–La/Yb–km.

Application of these equations yields mean absolute differences between crustal thicknesses calculated

with individual Sr/Y and La/Yb of ~6 km. Paired Sr/Y–La/Yb calibration yields absolute differences of ~3

km compared to Sr/Y and La/Yb. Discrepancies in crustal thickness estimates between Sr/Y and La/Yb using

the original calibrations in Profeta et al. (2015) are highly variable, with an average of ~21 km, and

are largely the result of extreme crustal thickness estimates (>100 km) resulting from linear

transformation of high (>70) Sr/Y ratios (supplemental material [see footnote 1]); such discrepancies

are likely due to a lack of crustal thickness estimates from orogens with rocks that are young enough

(i.e., Pleistocene or younger) to include in the empirical calibration.

For geologic interpretation, we use results from multiple linear regression of Sr/Y–La/Yb–km to calculate

temporal changes in crustal thickness (Figs. 3B–3D). Results show a decrease in crustal thickness from

36 to 30 km between 180 and 170 Ma. Available data between 170 and 100 Ma include a single estimate of

~55 km at ca. 135 Ma. Crustal thickness decreased to 30–50 km by ca. 60 Ma, then increased to 60–70 km

by ca. 40 Ma (Fig. 3). The two different methods for calculating temporal trends in crustal thickness

(Gaussian kernel regression and linear regression) produced similar results (Figs. 3C–3D). The Gaussian

kernel regression model produces a smooth record of crustal thickness change that decreases from ~35 to

~30 km between 180 and 165 Ma, decreases from ~54 to ~40 km between 90 and 75 Ma, increases from ~40 to

~70 km between 60 and 40 Ma, and remains steady-state from 40 Ma to present; the large uncertainty

window between 160 and 130 Ma is due to the bootstrap resampling occasionally missing the single data

point at ca. 135 Ma (Fig. 3C). Linear rates of crustal thickness change indicate thinning at ~0.7 mm/a

between 180 and 170 Ma, thinning at ~0.8 mm/a between 90 and 65 Ma, and thickening at ~1.3 mm/a between

60 and 30 Ma (Fig. 3D).

Figure

3

Figure

3

Results of new Sr/Y and La/Yb proxy calibration applied to data from the Tibetan Magmatism Database

(Chapman and Kapp, 2017) located in the eastern Gangdese Mountains in southern Tibet. (A) Filtered Sr/Y

and La/Yb data extracted from 29 to 31°N and 89 to 92°W. (B) Values from part A converted to crustal

thickness using Equations 1, 2, and 3 (see text). (C–D) Temporal trends based on multiple linear

regression of Sr/Y–La/Yb–km; trends are calculated from 10,000 bootstrap resamples, with replacement.

(C) Gaussian kernel regression model to determine a continuous thickening history. (D) Linear regression

to determine linear rates for critical time intervals.

Discussion

Early to Middle Jurassic crustal thickness in southern Tibet was controlled by the northward subduction

of Neo-Tethys oceanic lithosphere (Guo et al., 2013) in an Andean-type orogen that existed until the

Early Cretaceous (Zhang et al., 2012), punctuated by backarc extension between 183 and 174 Ma (Wei et

al., 2017). The latter is consistent with our results of minor crustal thinning from ~36 to ~30 km

between 180 and 170 Ma (Figs. 3B–3D) and supports models invoking a period of Neo-Tethys slab rollback

(i.e., trench retreat), southward rifting of the Zedong arc from the Gangdese arc, and a phase of

supra-subduction zone ophiolite generation along the southern margin of Asia (Fig. 4A) (Kapp and

DeCelles, 2019). Rocks with ages between 170 and 100 Ma are limited to a single data point at ca. 135 Ma

and yield estimates of ~55 km thick crust (Fig. 3B–3D). This is consistent with geologic mapping and

geochronological data that suggest that major north-south crustal shortening took place in the Early

Cretaceous along east-west–striking thrust faults in southern Tibet (Murphy et al., 1997).

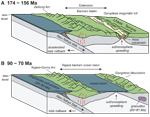

Figure

4

Figure

4

Tectonic interpretation after Kapp and DeCelles (2019). (A) Middle–Late Jurassic accelerated slab

rollback during formation of the Zedong Arc drives the opening of an extensional backarc basin. This is

consistent with the generation of the late-stage, juvenile (asthenosphere derived) Yeba volcanics (Liu

et al., 2018). (B) Late Cretaceous slab rollback results in the opening of a backarc ocean basin.

The strongest crustal thinning trend in our results occurs between 90 and 70 Ma at a rate of ~0.8 mm/a

(Fig. 3D). Crustal thinning takes place after major crustal shortening (and thickening) documented in

the southern Lhasa terrane prior to and up until ca. 90 Ma (Kapp et al., 2007; Volkmer et al., 2007; Lai

et al., 2019), following shallow marine carbonate deposition during the Aptian–Albian (126–100 Ma)

across much of the Lhasa terrane (Leeder et al., 1988; Leier et al., 2007). Late Cretaceous crustal

thinning to ~40 km (closer to the average thickness of continental crust) supports models that invoke

Late Cretaceous extension and Neo-Tethys slab rollback that led to the development of an

intracontinental backarc basin in southern Tibet and southward rifting of a southern portion of the

Gangdese arc (referred to as the Xigaze arc) from the southern Asian continental margin (Kapp and

DeCelles, 2019) (Fig. 4B). If a backarc ocean basin indeed opened between Asia and the rifted Xigaze arc

during this time, it would have profound implications for Neo-Tethyan paleogeographic reconstructions

and the history of suturing between India and Asia; this remains to be tested by future field-based

studies.

Paleogene crustal thickness estimates indicate monotonic crustal thickening at rates of ~1.3 mm/a to

>60 km following the collision between India and Asia. This is in contrast to models explaining the

development of modern high elevation resulting from the removal of mantle lithosphere during the Miocene

or Pliocene (Dewey et al., 1988; England and Houseman, 1988; Harrison et al., 1992; Molnar et al.,

1993). The timing of crustal thickening in the late Paleogene temporally corresponds to the termination

of arc magmatism in southern Tibet at 40–38 Ma and may indicate that the melt-fertile upper-mantle wedge

was displaced to the north by shallowing subduction of Indian continental lithosphere (Laskowski et al.,

2017). Crustal thickening during the Paleogene may be attributed to progressive shortening and southward

propagation (with respect to India) of the Tibetan-Himalayan orogenic wedge as Indian crust was accreted

in response to continuing convergence. We interpret that thickening depended mainly on the flux of crust

into the orogenic wedge, as convergence between India and Asia slowed by more than 40% between 20 and 10

Ma (Molnar and Stock, 2009), subsequent to peak crustal thickening rates between 60 and 30 Ma.

Estimates of crustal thickness based on Sr/Y and La/Yb differ both in time and space compared to

estimates using radiogenic isotopes. Determining crustal thickness from Nd or Hf relies on an extension

of the flux-temperature model of DePaolo et al. (1992), which calculates the ambient crustal temperature

and assimilation required to produce measured isotopic compositions (e.g., Hammersley and DePaolo, 2006)

assuming a depleted asthenospheric melt source with no contribution from the mantle lithosphere; crustal

thickness is then calculated based on an assumed geothermal gradient on the premise that a deeper,

hotter Moho would result in more crustal assimilation than a shallower, cooler Moho. In addition to

using La/Yb to estimate Cenozoic crustal thickness, DePaolo et al. (2019) use the flux-temperature model

to suggest that crustal thickening in southern Tibet was nonuniform based on Nd isotopes. Specifically,

they estimate crustal thickness of 25–35 km south of 29.8° N until 45 Ma, followed by major crustal

thickening to 55–60 km by the early to middle Miocene. Critically, they suggest that north of 29.9° N

the crust was at near modern thickness before 45 Ma and that there was a crustal discontinuity between

these two domains, which Alexander et al. (2019) later interpret along orogenic strike to the east based

on Hf isotopic data. In contrast, our results show that crustal thickening was already well under way by

45 Ma, potentially near modern crustal thickness, and with no dependence on latitude (Figs. 3B–3D and

supplemental material [see footnote 1]). Radiogenic isotopes such as Nd and Hf are not directly

controlled by crustal thickness and concomitant pressure changes. Rather, variability in Hf and Nd is

likely due to complex crustal assimilation, to which pressure-based (not temperature-based) proxies such

as Sr/Y and La/Yb from rocks filtered following Profeta et al. (2015) are less sensitive.

Crustal thickness of 65–70 km between 44 and 10 Ma based on trace-element geochemistry is similar to

modern crustal thickness of ~70 km estimated from geophysical methods (Owens and Zandt, 1997; Nábělek et

al., 2009) and are 10–20 km less than upper estimates of 80–85 km (Wittlinger et al., 2004; Xu et al.,

2015). Upper-crustal shortening persisted in southern Tibet until mid-Miocene time, but coeval rapid

erosion (Copeland et al., 1995) may have maintained a uniform crustal thickness. Our results are

inconsistent with models that invoke net crustal thinning via orogenic collapse (Dewey, 1988) beginning

in the Miocene and continuing to present day (Ge et al., 2015). Rather, our results are consistent with

interpretations of thick crust in southern Tibet by middle Eocene time (Aikman et al., 2008; Pullen et

al., 2011), which continued to thicken at depth due to the ongoing mass addition of underthrusting India

(DeCelles et al., 2002) before, during, and after the Miocene onset of extension in southern Tibet

(e.g., Harrison et al., 1995; Kapp et al., 2005; Sanchez et al., 2013). We favor a model in which

continued crustal thickening at depth is balanced by upper crustal thinning (Kapp and Guynn, 2004;

DeCelles et al., 2007; Styron et al., 2015), with excess mass potentially evacuated by ductile lower

crustal flow (Royden et al. 1997). In this view, late Miocene–Pliocene acceleration of rifting in

southern Tibet (Styron et al., 2013; Sundell et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2019) is a consequence of the

position of the leading northern tip of India (Styron et al., 2015), because this region experiences

localized thickening at depth, which in turn increases the rate of upper crustal extension in order to

maintain isostatic equilibrium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Hawkesworth, Allen Glazner, two anonymous reviewers, and editor Peter Copeland for their

detailed critique of this work. We also thank Michael Taylor and Richard Styron for informal reviews;

Sarah George and Gilby Jepson for insightful discussions on proxies for crustal thickness; and Caden

Howlett and Aislin Reynolds for discussions of Tibetan tectonics during the 2019 field season as this

research was formulated. KES was partially supported by the National Science Foundation (EAR-1649254) at

the Arizona LaserChron Center. M.N.D. acknowledges support from National Science Foundation grant EAR

1725002 and the Romanian Executive Agency for Higher Education, Re-search, Development and Innovation

Funding project PN-III-P4-ID-PCCF-2016-0014.

References Cited

- Aikman, A.B., Harrison, T.M., and Lin, D., 2008, Evidence for early (>44 Ma) Himalayan crustal

thickening, Tethyan Himalaya, southeastern Tibet: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 274, no.

1–2, p. 14–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.06.038.

- Aitchison, J.C., Ali, J.R., and Davis, A.M., 2007, When and where did India and Asia collide?:

Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, v. 112, no. B5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004706.

- Alexander, E.W., Wielicki, M.M., Harrison, T.M., DePaolo, D.J., Zhao, Z.D., and Zhu, D.C., 2019, Hf

and Nd isotopic constraints on pre-and syn-collisional crustal thickness of southern Tibet: Journal

of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, v. 124, no. 11, p. 11,038–11,054, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017696.

- Argand, E., 1922, June. La tectonique de l’Asie: Conférence faite à Bruxelles, le 10 août 1922.

- Chapman, J.B., and Kapp, P., 2017, Tibetan magmatism database: Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems,

v. 18, no. 11, p. 4229–4234, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GC007217.

- Chapman, J.B., Ducea, M.N., DeCelles, P.G., and Profeta, L., 2015, Tracking changes in crustal

thickness during orogenic evolution with Sr/Y: An example from the North American Cordillera:

Geology, v. 43, no. 10, p. 919–922, https://doi.org/10.1130/G36996.1.

- Copeland, P., Harrison, T.M., Pan, Y., Kidd, W.S.F., Roden, M., and Zhang, Y., 1995, Thermal

evolution of the Gangdese batholith, southern Tibet: A history of episodic unroofing: Tectonics, v.

14, no. 2, p. 223–236, https://doi.org/10.1029/94TC01676.

- Currie, B.S., Rowley, D.B., and Tabor, N.J., 2005, Middle Miocene paleoaltimetry of southern Tibet:

Implications for the role of mantle thickening and delamination in the Himalayan orogen: Geology, v.

33, no. 3, p. 181–184, https://doi.org/10.1130/G21170.1.

- DeCelles, P.G., Robinson, D.M., and Zandt, G., 2002, Implications of shortening in the Himalayan

fold-thrust belt for uplift of the Tibetan Plateau: Tectonics, v. 21, no. 6, p. 12-1–12-25, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001TC001322.

- DeCelles, P.G., Quade, J., Kapp, P., Fan, M., Dettman, D.L., and Ding, L., 2007, High and dry in

central Tibet during the Late Oligocene: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 253, no. 3–4, p.

389–401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.11.001.

- DePaolo, D.J., Perry, F.V., and Baldridge, W.S., 1992, Crustal versus mantle sources of granitic

magmas: A two-parameter model based on Nd isotopic studies: Transactions of the Royal Society of

Edinburgh. Earth Sciences, v. 83, no. 1–2, p. 439–446, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263593300008117.

- DePaolo, D.J., Harrison, T.M., Wielicki, M., Zhao, Z., Zhu, D.C., Zhang, H., and Mo, X., 2019,

Geochemical evidence for thin syn-collision crust and major crustal thickening between 45 and 32 Ma

at the southern margin of Tibet: Gondwana Research, v. 73, p. 123–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2019.03.011.

- Dewey, J.F., 1988, Extensional collapse of orogens: Tectonics, v. 7, no. 6, p. 1123–1139, https://doi.org/10.1029/TC007i006p01123.

- Dewey, J.F., Shackleton, R.M., Chengfa, C., and Yiyin, S., 1988, The tectonic evolution of the

Tibetan Plateau: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical

and Physical Sciences, v. 327, no. 1594, p. 379–413.

- Ding, L., Xu, Q., Yue, Y., Wang, H., Cai, F., and Li, S., 2014, The Andean-type Gangdese Mountains:

Paleoelevation record from the Paleocene–Eocene Linzhou Basin: Earth and Planetary Science Letters,

v. 392, p. 250–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.01.045.

- Ellam, R.M., 1992, Lithospheric thickness as a control on basalt geochemistry: Geology, v. 20, no.

2, p. 153–156, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1992)020<0153:LTAACO>2.3.CO;2.

- England, P.C., and Houseman, G.A., 1988, The mechanics of the Tibetan Plateau: Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, v. 326,

no. 1589, p. 301–320.

- Farner, M.J., and Lee, C.T.A., 2017, Effects of crustal thickness on magmatic differentiation in

subduction zone volcanism: A global study: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 470, p. 96–107,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.04.025.

- Ge, W.P., Molnar, P., Shen, Z.K., and Li, Q., 2015, Present-day crustal thinning in the southern and

northern Tibetan plateau revealed by GPS measurements: Geophysical Research Letters, v. 42, no. 13,

p. 5227–5235, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL064347.

- Guo, L., Liu, Y., Liu, S., Cawood, P.A., Wang, Z., and Liu, H., 2013, Petrogenesis of Early to

Middle Jurassic granitoid rocks from the Gangdese belt, Southern Tibet: Implications for early

history of the Neo-Tethys: Lithos, v. 179, p. 320–333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2013.06.011.

- Hammersley, L., and DePaolo, D.J., 2006, Isotopic and geophysical constraints on the structure and

evolution of the Clear Lake volcanic system: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, v. 153,

no. 3–4, p. 331–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.12.003.

- Harrison, T.M., Copeland, P., Kidd, W.S.F., and Lovera, O.M., 1995, Activation of the

Nyainqentanghla shear zone: Implications for uplift of the southern Tibetan Plateau: Tectonics, v.

14, no. 3, p. 658–676, https://doi.org/10.1029/95TC00608.

- Heaman, L.M., Bowins, R., and Crocket, J., 1990, The chemical composition of igneous zircon suites:

Implications for geochemical tracer studies: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, v. 54, no. 6, p.

1597–1607, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(90)90394-Z.

- Hildreth, W., and Moorbath, S., 1988, Crustal contributions to arc magmatism in the Andes of central

Chile: Contributions to Mineralogy and Pe-trology, v. 98, no. 4, p. 455–489, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00372365.

- Horová, I., Kolacek, J., and Zelinka, J., 2012, Kernel smoothing in MATLAB: Theory and practice of

kernel smoothing: Toh Tuck Link, Singa-pore, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., p. 137–178.

- Hu, F., Ducea, M.N., Liu, S., and Chapman, J.B., 2017, Quantifying crustal thickness in continental

collisional belts: Global perspective and a geologic application: Scientific Reports, v. 7, no. 1,

7058, p. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07849-7.

- Hu, F., Wu, F., Chapman, J.B., Ducea, M.N., Ji, W., and Liu, S., 2020, Quantitatively tracking the

elevation of the Tibetan Plateau since the Creta-ceous: Insights from whole-rock Sr/Y and La/Yb

ratios: Geophysical Research Letters, v. 47, no. 15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089202.

- Hu, X., Wang, J., BouDagher-Fadel, M., Garzanti, E., and An, W., 2016, New insights into the timing

of the India–Asia collision from the Paleogene Quxia and Jialazi formations of the Xigaze forearc

basin, South Tibet: Gondwana Research, v. 32, p. 76–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2015.02.007.

- Ingalls, M., Rowley, D., Olack, G., Currie, B., Li, S., Schmidt, J., Tremblay, M., Polissar, P.,

Shuster, D.L., Lin, D., and Colman, A., 2018, Paleocene to Pliocene low-latitude, high-elevation

basins of southern Tibet: Implications for tectonic models of India-Asia collision, Cenozoic

climate, and geochemical weathering: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 130, no. 1–2, p.

307–330, https://doi.org/10.1130/B31723.1.

- Kapp, J.L.D., Harrison, T.M., Kapp, P., Grove, M., Lovera, O.M., and Lin, D., 2005, Nyainqentanglha

Shan: A window into the tectonic, thermal, and geochemical evolution of the Lhasa block, southern

Tibet: Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, v. 110, B8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JB003330.

- Kapp, P., and DeCelles, P.G., 2019, Mesozoic–Cenozoic geological evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan

orogen and working tectonic hypotheses: American Journal of Science, v. 319, no. 3, p. 159–254,

https://doi.org/10.2475/03.2019.01.

- Kapp, P., and Guynn, J.H., 2004, Indian punch rifts Tibet: Geology, v. 32, no. 11, p. 993–996, https://doi.org/10.1130/G20689.1.

- Kapp, P., DeCelles, P.G., Gehrels, G.E., Heizler, M., and Ding, L., 2007, Geological records of the

Lhasa-Qiangtang and Indo-Asian collisions in the Nima area of central Tibet: Geological Society of

America Bulletin, v. 119, no. 7–8, p. 917–933, https://doi.org/10.1130/B26033.1.

- Kay, S.M., and Mpodozis, C., 2002, Magmatism as a probe to the Neogene shallowing of the Nazca plate

beneath the modern Chilean flat-slab: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, v. 15, no. 1, p.

39–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-9811(02)00005-6.

- Lai, W., Hu, X., Garzanti, E., Sun, G., Garzione, C.N., Fadel, M.B., and Ma, A., 2019, Initial

growth of the Northern Lhasaplano, Tibetan Plateau in the early Late Cretaceous (ca. 92 Ma):

Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 131, no. 11–12, p. 1823–1836, https://doi.org/10.1130/B35124.1.

- Laskowski, A.K., Kapp, P., Ding, L., Campbell, C., and Liu, X., 2017, Tectonic evolution of the

Yarlung suture zone, Lopu Range region, southern Tibet: Tectonics, v. 36, no. 1, p. 108–136, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016TC004334.

- Leeder, M.R., Smith, A.B., and Jixiang, Y., 1988, Sedimentology, palaeoecology and

palaeoenvironmental evolution of the 1985 Lhasa to Golmud Geotraverse: Philosophical Transactions of

the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, v. 327, no. 1594, p.

107–143.

- Leier, A.L., Kapp, P., Gehrels, G.E., and DeCelles, P.G., 2007, Detrital zircon geochronology of

Carboniferous–Cretaceous strata in the Lhasa terrane, Southern Tibet: Basin Research, v. 19, no. 3,

p. 361–378, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2117.2007.00330.x.

- Liu, Z.C., Ding, L., Zhang, L.Y., Wang, C., Qiu, Z.L., Wang, J.G., Shen, X.L., and Deng, X.Q., 2018,

Sequence and petrogenesis of the Jurassic volcanic rocks (Yeba Formation) in the Gangdese arc,

southern Tibet: Implications for the Neo-Tethyan subduction: Lithos, v. 312–313, p. 72–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2018.04.026.

- Molnar, P., and Stock, J.M., 2009, Slowing of India’s convergence with Eurasia since 20 Ma and its

implications for Tibetan mantle dynamics: Tectonics, v. 28, no. 3, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008TC002271.

- Molnar, P., and Tapponnier, P., 1978, Active tectonics of Tibet: Journal of Geophysical Research.

Solid Earth, v. 83, B11, p. 5361–5375, https://doi.org/10.1029/JB083iB11p05361.

- Molnar, P., England, P., and Martinod, J., 1993, Mantle dynamics, uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, and

the Indian monsoon: Reviews of Geophysics, v. 31, no. 4, p. 357–396, https://doi.org/10.1029/93RG02030.

- Murphy, M.A., Yin, A., Harrison, T.M., Durr, S.B., Ryerson, F.J., and Kidd, W.S.F., 1997, Did the

Indo-Asian collision alone create the Tibetan plateau?: Geology, v. 25, no. 8, p. 719–722, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0719:DTIACA>2.3.CO;2.

- Nábělek, J., Hetényi, G., Vergne, J., Sapkota, S., Kafle, B., Jiang, M., Su, H., Chen, J., and

Huang, B.S., 2009, Underplating in the Himalaya-Tibet collision zone revealed by the Hi-CLIMB

experiment: Science, v. 325, no. 5946, p. 1371–1374, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1167719.

- Owens, T.J., and Zandt, G., 1997, Implications of crustal property variations for models of Tibetan

plateau evolution: Nature, v. 387, no. 6628, p. 37–43, https://doi.org/10.1038/387037a0.

- Paterson, S.R., and Ducea, M.N., 2015, Arc magmatic tempos: Gathering the evidence: Elements, v. 11,

no. 2, p. 91–98, https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.11.2.91.

- Profeta, L., Ducea, M.N., Chapman, J.B., Paterson, S.R., Gonzales, S.M.H., Kirsch, M., Petrescu, L.,

and DeCelles, P.G., 2015, Quantifying crustal thickness over time in magmatic arcs: Scientific

Reports, v. 5, 17786, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17786.

- Pullen, A., Kapp, P., Gehrels, G.E., Ding, L., and Zhang, Q., 2011, Metamorphic rocks in central

Tibet: Lateral variations and implications for crustal structure: Geological Society of America

Bulletin, v. 123, no. 3–4, p. 585–600, https://doi.org/10.1130/B30154.1.

- Rowley, D.B., 1996, Age of initiation of collision between India and Asia: A review of stratigraphic

data: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 145, no. 1–4, p. 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(96)00201-4.

- Royden, L.H., Burchfiel, B.C., King, R.W., Wang, E., Chen, Z., Shen, F., and Liu, Y., 1997, Surface

deformation and lower crustal flow in eastern Tibet: Science, v. 276, 5313, p. 788–790, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.276.5313.788.

- Sanchez, V.I., Murphy, M.A., Robinson, A.C., Lapen, T.J., and Heizler, M.T., 2013, Tectonic

evolution of the India–Asia suture zone since Mid-dle Eocene time, Lopukangri area, south-central

Tibet: Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, v. 62, p. 205–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.09.004.

- Styron, R., Taylor, M., and Okoronkwo, K., 2010, Database of active structures from the Indo-Asian

collision: Eos, v. 91, no. 20, p. 181–182, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010EO200001.

- Styron, R.H., Taylor, M.H., Sundell, K.E., Stockli, D.F., Oalmann, J.A., Möller, A., McCallister,

A.T., Liu, D., and Ding, L., 2013, Miocene initiation and acceleration of extension in the South

Lunggar rift, western Tibet: Evolution of an active detachment system from structural mapping and

(U-Th)/He thermochronology: Tectonics, v. 32, no. 4, p. 880–907, https://doi.org/10.1002/tect.20053.

- Styron, R., Taylor, M., and Sundell, K., 2015, Accelerated extension of Tibet linked to the

northward underthrusting of Indian crust: Nature Geoscience, v. 8, no. 2, p. 131–134, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2336.

- Sundell, K.E., Taylor, M.H., Styron, R.H., Stockli, D.F., Kapp, P., Hager, C., Liu, D., and Ding,

L., 2013, Evidence for constriction and Pliocene acceleration of east-west extension in the North

Lunggar rift region of west central Tibet: Tectonics, v. 32, no. 5, p. 1454–1479, https://doi.org/10.1002/tect.20086.

- Taylor, M., and Yin, A., 2009, Active structures of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen and their

relationships to earthquake distribution, contemporary strain field, and Cenozoic volcanism:

Geosphere, v. 5, no. 3, p. 199–214, https://doi.org/10.1130/GES00217.1.

- van Hinsbergen, D.J., Lippert, P.C., Dupont-Nivet, G., McQuarrie, N., Doubrovine, P.V., Spakman, W.,

and Torsvik, T.H., 2012, Greater India Basin hypothesis and a two-stage Cenozoic collision between

India and Asia: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, v.

109, no. 20, p. 7659–7664, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117262109.

- Volkmer, J.E., Kapp, P., Guynn, J.H., and Lai, Q., 2007, Cretaceous–Tertiary structural evolution of

the north central Lhasa terrane, Tibet: Tectonics, v. 26, no. 6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005TC001832.

- Wei, Y., Zhao, Z., Niu, Y., Zhu, D.C., Liu, D., Wang, Q., Hou, Z., Mo, X., and Wei, J., 2017,

Geochronology and geochemistry of the Early Juras-sic Yeba Formation volcanic rocks in southern

Tibet: Initiation of back-arc rifting and crustal accretion in the southern Lhasa Terrane: Lithos,

v. 278-281, p. 477–490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2017.02.013.

- Wen, D.R., Liu, D., Chung, S.L., Chu, M.F., Ji, J., Zhang, Q., Song, B., Lee, T.Y., Yeh, M.W., and

Lo, C.H., 2008, Zircon SHRIMP U-Pb ages of the Gangdese Batholith and implications for Neotethyan

subduction in southern Tibet: Chemical Geology, v. 252, no. 3–4, p. 191–201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.03.003.

- Wittlinger, G., Vergne, J., Tapponnier, P., Farra, V., Poupinet, G., Jiang, M., Su, H., Herquel, G.,

and Paul, A., 2004, Teleseismic imaging of subducting lithosphere and Moho offsets beneath western

Tibet: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 221, no. 1–4, p. 117–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00723-4.

- Wolff, R., Hetzel, R., Dunkl, I., Xu, Q., Bröcker, M., and Anczkiewicz, A.A., 2019, High-angle

normal faulting at the Tangra Yumco Graben (Southern Tibet) since ~15 Ma: The Journal of Geology, v.

127, no. 1, p. 15–36, https://doi.org/10.1086/700406.

- Xu, Q., Zhao, J., Yuan, X., Liu, H., and Pei, S., 2015, Mapping crustal structure beneath southern

Tibet: Seismic evidence for continental crustal underthrusting: Gondwana Research, v. 27, no. 4, p.

1487–1493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2014.01.006.

- Yan, D., Li, M., Bi, W., Weng, B., Qin, T., Wang, J., and Do, P., 2019, A data set of inland lake

catchment boundaries for the Qiangtang Plateau: Scientific Data, v. 6, no. 1, p. 1–11.

- Yin, A., and Harrison, T.M., 2000, Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen: Annual Review

of Earth and Planetary Sciences, v. 28, no. 1, p. 211–280, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.211.

- Zhang, K.J., Zhang, Y.X., Tang, X.C., and Xia, B., 2012, Late Mesozoic tectonic evolution and growth

of the Tibetan plateau prior to the Indo-Asian collision: Earth-Science Reviews, v. 114, no. 3–4,

p. 236–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.06.001.

- Zhu, D.C., Wang, Q., Cawood, P.A., Zhao, Z.D., and Mo, X.X., 2017, Raising the Gangdese mountains in

southern Tibet: Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, v. 122, no. 1, p. 214–223, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013508.