The ‘Ike Wai Project

Since 2017, we have been piloting a small IDP program as part of ‘Ike Wai, a multidisciplinary research

project focused on water resources and sustainability at the University of Hawai‘i. Funded by the

National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, ‘Ike Wai

(Hawaiian for water knowledge) includes a capacity-building initiative to develop a diverse

local workforce in hydrology and related fields. IDPs form part of a larger professional development

program that includes holistic mentoring, research training, and broad skills development.

‘Ike Wai graduate students and postdocs develop their IDP with guidance from both their research advisor

and an external professional development (PD) mentor. The PD mentor, a faculty/staff member selected by

the trainee from outside their discipline, serves as an additional resource and perspective. All parties

work together to ensure the action plan is both useful and realistic. We emphasize that completing an

IDP is a trainee-driven process—they are ultimately responsible for defining and communicating their

future goals and aspirations and soliciting feedback on their plan.

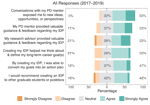

Survey results indicate students particularly value their interactions with their PD mentor, and a

majority agreed or strongly agreed that completing the IDP helped them think about their long-term

career goals (Fig. 1). In spite of the time required to complete and update their IDP on a regular

basis, only 16% said they would not recommend an IDP to other students or postdocs, consistent with what

we hear as facilitators—most find the process useful and are ultimately glad to have done it. Similarly,

81% of ‘Ike Wai advisors and PD mentors agreed they would recommend IDPs, with 90% agreeing that

completing an IDP helped students think about their academic and long-term career goals (GSA

Supplemental Data Fig. S11).

Figure

1

Figure

1

Aggregated results from our annual, anonymous survey of graduate students (2017–2019) (

n = 21).

Percentages shown correspond to the total responses for disagree or strongly disagree (left), neutral

(center), and agree or strongly agree (right). IDP—individual development plans; PD—professional

development mentor.

While possibly coincidental rather than causal, we note that the trainees in our IDP program have shown

exceptional leadership, taking on responsibilities beyond that of typical graduate students. Examples

include convening conference sessions and workshops, requesting representation on the project’s

leadership committee, mentoring undergraduates, and taking a leading role in drafting project reports,

planning fieldwork, and managing lab budgets.

Alumni report that they value, and continue to use, the goal-setting skills they learned from IDPs. As

recent graduate Julie U‘ilani Au wrote, “By setting personal and professional goals for myself, I have

been able to gain a clear vision of what I want to do with my time and my career. Whenever I feel

overwhelmed or confused, I think back to the IDP structure and make goals that I can hold myself

accountable to.”

Implementation

Based on our experiences with this ongoing pilot program, we outline a few key considerations for those

interested in implementing their own IDP program.

A Flexible Template

We created a simple custom form suited to the ‘Ike Wai project that includes six core competencies:

Research, Teaching and Mentoring, Leadership, Communication, Career Development, and Place and Culture

(Supplemental Data Fig. S3). The last category was added to formalize the importance and relevance of

cultural knowledge and skills. The project has an unusually diverse student cohort, including a high

proportion of Native Hawaiians, women, and others from historically underrepresented groups. Moreover, a

significant project component entails engaging with a diverse community of landowners and other

stakeholders, which requires an additional set of knowledge and skills that were not well captured by

most standard IDP templates. Although we provide forms, we also give trainees the option of using

alternative formats as long as they capture the critical elements of an effective action plan: having

specific, actionable milestones with clearly defined outputs and a realistic timeline. While many

students stick to the provided template, some have opted to use an online calendar or custom color-coded

timelines. We also provide links to online IDP platforms with extensive career exploration tools as

additional resources (e.g., myIDP).

Expanded Mentoring Network

According to our survey results, our trainees highly value PD mentors. The additional time burden on the

mentor is minimal (most report spending ~1 hr or less per term; Supplemental Data Fig. S2), and while

students could cultivate such relationships themselves, providing a formal match removes some of the

psychological barriers to asking for help. This second mentor may play a particularly important role if

the advisor-advisee relationship is strained, or their PD goals are poorly aligned with their research

project. We also note this role has been particularly useful for underrepresented students seeking the

guidance of someone from a similar background and shared cultural values. Particularly in the

geosciences, one of the least diverse STEM fields (NSF, 2019), connecting students with faculty members

outside their immediate discipline is one option for expanding and diversifying their support network.

Advisor Buy-In

Some of our experiences and feedback point to the importance of advisor buy-in and engagement, consistent

with other studies that find advisees are more likely to value the IDP process if their advisor also

does (e.g., Hobin et al., 2014). In other words, this process is not a fix for a disengaged advisor or

one who is dismissive of non-academic careers. However, we note the potential power of the IDP process

to open a dialogue on future career plans and perhaps dispel incorrect assumptions advisors may have

about an advisee’s goals and aspirations. Everyone benefits from starting this conversation early and

helping trainees build the skills they will need for their future, whatever their chosen path.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by National Science Foundation grant OIA-1557349. This is SOEST contribution #10949.

References Cited

- Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), 2002, Individual Development Plan

for Postdoctoral Fellows: Bethesda, Maryland.

- Gollwitzer, P.M., 1999, Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans: The American

Psychologist, v. 54, p. 493–503, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493.

- Hobin, J.A., Clifford, P.S., Dunn, B.M., Rich, S., and Justement, L.B., 2014, Putting PhDs to work:

Career planning for today’s scientist: CBE Life Sciences Education, v. 13, no. 1, p. 49–53,

https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe-13-04-0085.

- NASEM, 2019, The Science of Effective Mentorship in STEMM: Washington, D.C., National Academies

Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/25568.

- NSF, 2019, Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in STEM: Arlington, Virginia, National

Science Foundation Special Report NSF 19-304, https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/women.

- Tsai, J.W., Vanderford, N.L., and Muindi, F., 2018, Optimizing the utility of the individual

development plan for trainees in the biosciences: Nature Biotechnology, v. 36, no. 6, p. 552–553,

https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4155.

- Vincent, B.J., Scholes, C., Staller, M.V., Wunderlich, Z., Estrada, J., Park, J., Bragdon, M.D.J.,

Rivera, F.L., Bietta, K.M., and DePace, A.H., 2015, Yearly planning meetings: Individualized

development plans aren’t just more paperwork: Molecular Cell, v. 58,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.025.